Last week, I attended the annual meeting of the Global Alliance for the Science of Learning, of which the Chartered College of Teaching is a founding member, at UNESCO headquarters in Paris. I look forward to this meeting every year as it is a fantastic opportunity to hear from colleagues across the world about their research into the science of learning and how they are implementing findings in their contexts. This year, I was particularly pleased to have been asked to chair an opening panel discussion with four practitioners, as I have been advocating for the need to include more practitioner voices in the discussions. Currently, only 4% of the Global Alliance members are classroom practitioners — a shortcoming we need to address urgently, and something that I intend to work towards improving over the years to come.

The panellists presented evidence from Panama (Kevin Bartlett), Australia (Chris Duncan), the United States (Glenn Whitman) and Germany (Oliver Kunkel) and we had a great discussion about the role of teachers in implementing insights from research in their classrooms, the skills teachers need to do so successfully, the importance of re-professionalising, not de-professionalising teachers in the context of evidence-informed practice and the need for a two-way dialogue between research and practice. Our panel was extremely well received, including by leading education researchers from across the world, showing just how important it is to have teachers and school leaders represented in these discussions.

A few additional key themes emerged in our discussions across the two days, which I will tackle in the remainder of this blog post.

Definitions of learning

The need to define what we actually mean by ‘learning’ and, by extension, what we mean by the ‘science of learning’, emerged as a strong theme over the course of the two days. There clearly wasn’t a consensus in the room, which is illustrated anecdotally by the definitions the practitioners on my panel provided when I asked them to define learning in their own words. To them, learning is:

“…the acquisition of a skill, knowledge or understanding that previously had not been acquired.”

“…those educational experiences, deliberate and unplanned, that make a human life go well.”

“…the acquisition and development of beneficial intelligence.”

“… the process of the consolidation and extension of conceptual understanding, competency and character.”

Notice how each of these definitions differ slightly but how not a single one stops at the acquisition of abstract knowledge. Everyone in the room probably had their own definition and understanding of learning and maybe we do not need a consensus, but we do need to be more explicit when discussing the ‘impact’ of research on ‘learning’ (even within specific subject areas) and therefore what the ‘science’ of ‘learning’ can and cannot tell us about classroom practice.

Typically, research looks at small sub-components of skills (e.g. the impact of rhythm on reading acquisition, the use of songs on vocabulary acquisition, implicit versus explicit vocabulary instruction, etc.), which is necessary to design valid experiments and measure change precisely. However, this necessary focus should not mean that other sub-components are disregarded, although it can sometimes be misinterpreted as such.

Essentially, we are at a place now where many of you may be after the Christmas holidays – we are sitting in front of a 1,000 (or more!) piece puzzle and trying to figure out how the different pieces go together to create the most effective and enjoyable learning experiences – with the one major difference that we are still missing quite a few pieces of our science of learning puzzle, which I hope won’t be the case for the ones you may receive at Christmas.

To move us ahead, I have therefore suggested that we start by capturing intended learning outcomes across a number of representative national curricula and subjects and map them against what we know from research about the most effective teaching strategies to achieve those outcomes and, by extension, what we don’t know.

Such an exercise will help to highlight that there is no such thing as one right teaching approach but that teachers need a repertoire of effective, evidence-informed teaching strategies in order to help students meet a range of different intended learning outcomes.

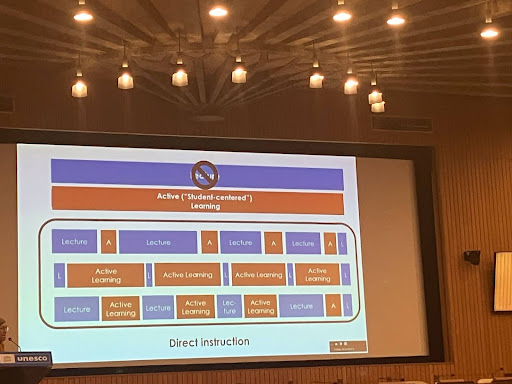

This leads me to Professor Barbara Oakley’s keynote lecture – one of the best lectures on the science of learning I have heard recently (or ever, to be honest) and I am not only saying so because Professor Oakley and I share the fate of having studied Russian and disliked maths (although she managed to overcome the latter, and her knowledge of Russian took her on many more adventures than mine ever did, but I digress… ). A lot of what Professor Oakley presented struck a chord but one slide particularly stuck with me, which is why I am sharing it with you here.

In this slide, Professor Oakley explained that high-quality teaching requires a combination of ‘lecture-style’ teaching with active, guided, student-centred approaches. Something most teachers probably know and likely already doing but somehow we have ended up (yet again) in a place where the two approaches are pitched against each other when they simply represent different pieces of a complex puzzle. It is not a question of either, or. It is a question of which approach, when, how and for what purpose. Presenting the two as mutually exclusive, often by misusing the associated terminology and misrepresenting research findings, may drive likes and followers on social media but it will not solve the learning crisis we are witnessing across the globe.

Motivation, engagement and belonging

This leads me to the next issue I discussed with delegates throughout the conference – motivation, engagement and belonging. For some reason, the finding that students who are engaged are not necessarily learning has led to some concluding that engagement does not matter, when this could not be further from the truth. Plenty of research, including some presented at this conference and two meta-analyses published earlier this year (Emslander et al., 2025, Ha et al., 2025), clearly show a reciprocal relationship between motivation, engagement, feelings of belonging, student-teacher relationships and learning – a relationship we cannot afford to ignore looking at the continued attendance crisis in England and elsewhere. Of course, reasons for students refusing to attend school are complex, and many have little or nothing to do with school itself, but that should not mean that we ignore notions of belonging, motivation or emotional safety, all of which are notoriously difficult to measure, based on the false interpretation that they do not matter.

Even the most effective teaching strategies lose their effectiveness when students are not in school to be taught using those strategies. We therefore have to consider how we can ensure that all students are happy in school and ready to learn, especially those for whom school is the only safe space in their lives.

Unintended consequences and lethal mutations

As I listened to presenters and panellists, I also reflected on potential unintended consequences of implementing science of learning strategies in classrooms. Representing an organisation based in a country where many teachers have been implementing insights from the science of learning for a while put me in a privileged but also tricky position. On the one hand, I was able to share some of the great practice that is happening across English schools, and indeed beyond England, but at the same time I also saw it as my responsibility to share some of the misconceptions or ‘lethal mutations’ that have resulted from attempts to implement the science of learning. Some examples include the implementation of retrieval practice at the start of every or most lessons in some schools or multi-academy trusts due to the belief that ‘more is better’ and regardless of the spacing of learning sequences; the promotion of lecture-style teaching only, rather than a combination of different approaches (see above); or the prevalence of teaching focused on the skills of reading to the detriment of other important aspects involved in developing competent and avid readers. None of these approaches are wrong or ineffective per se (quite the contrary – they have been found to be highly effective in supporting students’ learning), but as with everything in life, it turns out that you can have too much of a good thing.

Myriad factors are to blame for this. One is the impact agenda at universities. Researchers have to show real-life impact of their work, so naturally they will try and get their research in front of policymakers and argue for its usefulness in solving the learning crisis even though they will be the first to admit that their research is only presenting part of a much more complex picture. Policymakers themselves act partly based on evidence and partly based on their own worldviews or in line with party politics (Ellis and Conyard, 2024 discuss this issue brilliantly), so not all research may necessarily be translated into policy, regardless of its validity. Finally, practitioners may misinterpret research findings, assuming that more of one particular approach may lead to even better outcomes. Throw knowledge brokers in there, who advertently or inadvertently promote some approaches over others, and you have an explosive combination.

Strength in diversity

I would like to close with a reflection on diversity. The very nature of research funding and production means that views and findings from WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic) countries and individuals are strongly over-represented. This was also the case for this conference and the network more widely.

This is problematic for multiple reasons, many of which Dr Tutaleni Asino touched upon in his keynote address. Firstly, and probably quite obviously, there is the issue of context. We always talk about the importance of context when implementing research findings, and this issue is further exacerbated when trying to implement research findings from labs or even classroom research conducted in the Global North in the context of the Global South. Another issue that Dr Asino delved into was that of culture. Our culture and language defines how we conceptualise the world, including what we prioritise in education and research. Oracy is a notable example. Many African societies value oracy and storytelling significantly more than Western societies do, yet international, standardised assessments tend not to measure oracy outcomes (yet). As we are aiming to introduce oracy in the English curriculum, maybe we should turn to countries with a much richer, long-standing history of teaching about and through oracy? I think that we would have much to learn.

So, in short, this conference has showcased some of the great research that is happening in the science of learning and highlighted once more some of the great practice that is already happening in many schools in terms of implementing some of these research findings, but it‘s important to remember that evidence-informed education is like a 1000-piece puzzle with many missing pieces and solving it will take time and patience.

References

Ellis, N. and Conyard, G., 2024. Improving Education Policy Together: How It’s Made, Implemented, and Can Be Done Better. Routledge.

Emslander, V., Holzberger, D., Ofstad, S.B., Fischbach, A. and Scherer, R., 2025. Teacher–student relationships and student outcomes: A systematic second-order meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin.

Ha, C., McCarthy, M.F., Strambler, M.J. and Cipriano, C., 2025. Disentangling the Effects of Social and Emotional Learning Programs on Student Academic Achievement Across Grades 1–12: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, p.00346543251367769.