Written by Paul Middleton

Education research has been a cornerstone of my teaching career, and ever since my time as an early career teacher (ECT), I have sought new opportunities to push myself beyond the classroom. Some early highlights included being part of the Chartered Teacher Programme, delivering my first talk at an education conference, and completing a six-week international research study as part of my Churchill Fellowship. Ten years on, it remains integral to my work as Director of Teaching and Learning and underpins our current efforts towards achieving Research Mark Plus as a school.

But there was certainly a point a few years into my career where my momentum dropped, and I thought – what next? The fast-paced development of ECT years naturally slows down, and we may need a change from traditional approaches to CPD. So, after a lot of trial and error, here are five reflections to help supercharge your evidence-informed practice, revitalise your career, and take your professional development to the next level.

Tip 1: Reflect and Research

While this might not be the most groundbreaking way to start a series of supercharged tips, it is by far the most effective. After all, reflection is key to understanding the direction that professional development needs to go. As educators, we must continually reflect on our practice, the professional standards, the needs of our schools, and our future goals. The EEF’s reflection tool is perfect for this and is something that teachers should continue to do throughout their career, not just as an ECT. As explained in the Reflective Teaching series:

‘Reflecting on our own thinking and practices helps us to understand the complexity of the classroom choices and decisions that are faced routinely every day. It helps us to ensure that future actions can be justified; that we continue to be professionally accountable’.

Once we have reflected on our aims, we must gather as much evidence as possible. Whether it is flicking through back copies of Impact or scanning the Education Endowment Foundation’s summary reports, it is essential to critically evaluate the existing research and reflect on how this will work for your context. But remember that research can include everything from evaluating assessment data to conversations with colleagues; it does not have to be poring through piles of pedagogical literature. Personally, I value the opportunity to work with local and national networks to gather insights from similar and contrasting schools. For example, I am currently working on innovating our curriculum design and have utilised strategies from the ‘Rethinking Assessment’ consortium, the Next Generation Assessment Conference and conversations with local schools. Without these networks, it would be impossible to gain an understanding of how research on the page looks in practice. Taking the time to reflect on everything you have at your fingertips will ensure that future interventions have the solid foundations to succeed.

Tip 2: Think about the Why

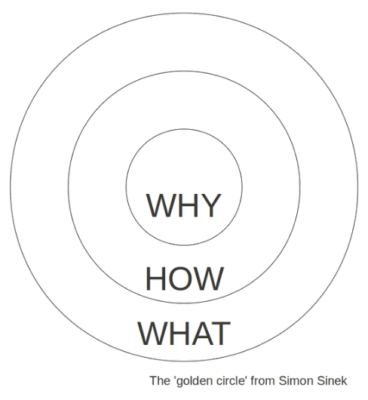

One of the most surprising directions my professional development has taken in the last decade is an increased focus on strategic thinking. As teachers, we often focus so much on each lesson and the four walls of our classrooms that we forget the importance of big-picture thinking. Whether it is communicating ideas to pupils, creating schemes of work, or designing whole-school interventions, we must start with the ‘Why?’ One champion of this is Simon Sinek, whose ‘Golden Circle’ model has transformed my approach to teaching and leadership in the last few years (Figure 1). As a History teacher, it led me to embed enquiry-based learning to improve literacy, and as a Head of Department, it encouraged me to rewrite our entire seven-year scheme of work to promote diversity, engagement, and innovation.

Recently, as a senior leader, it has helped shape our whole-school teaching and learning strategy, enabling it to be more purposeful and better embedded. Communicating the ‘why’ to others is the most important aspect of any intervention. For example, I have been amazed at how readily pupils have engaged with research surrounding retrieval practice, interleaving and dual coding. I hear pupils use these terms everywhere, from classrooms to lunch queues, and there is greater buy-in compared to our previous approaches to revision. Shifting from a culture of ‘You must do this…’ to ‘Here’s why you must do this…’ has been transformative and is something I wish I had learned earlier. For anyone with leadership aspirations, it is also incredibly valuable to develop this early on, so that you can approach future roles with greater confidence.

Tip 3: Understand the brain

My most valuable professional development in recent years was a six-month neuroscience course, which enabled me to gain a deeper understanding of the ‘why’. The research behind memory formed a significant part of the programme, complementing the work of familiar educationalists, such as Kate Jones and Poojah Agarwal. However, I was also exposed to unfamiliar quirks about the brain, which shaped my practice and helped me support colleagues and pupils. For example, I discovered that the connections in the brain that encourage cognition and reflection (within the prefrontal cortex) do not strengthen until late adolescence and adulthood, respectively (Figure 2). As such, younger pupils are more driven by emotion and risk, which can lead to sporadic behaviour and inconsistencies in work. Knowing this has helped inform my behaviour management strategies, such as focusing on praise and reward to mitigate poor behaviour or providing pupils time to reflect on negative actions before speaking to them. Even possessing a basic understanding of how the brain works can transform your teaching practice; it’s like leading an exercise class, knowing exactly how each movement will make the group fitter and stronger. The science behind the brain is also painfully complex, so it is incredibly humbling to put yourself back in the shoes of a confused and overwhelmed learner.

Figure 2: Changes in the Adolescent Brain, taken from B. J. Casey’s Neurobiology of the Adolescent Brain and Behavior (2010)

Tip 4: Go beyond the everyday

There are some areas of educational research that you will come across time and time again – retrieval practice, cognitive load theory, Rosenshine’s principles, and more. But what happens when you have exhausted this ‘Teaching 101’ reading list? At this point, take the opportunity to explore new areas of pedagogy that you had previously ignored. For example, the world of EdTech is a fast-moving and challenging area that I have enjoyed dipping into over recent years. As well as keeping abreast of new technologies via social media, I have attended conference sessions exploring AI and its role within education. It is useful to be proficient in these up-and-coming areas so you can allay colleague and parental fears and talk confidently with other stakeholders. I have also started to explore research beyond education, such as how to create successful teams, embed an organisational culture, and engage in challenging conversations. My first few years as a Head of Department were tough, as although I was confident being a classroom teacher, I had never learned how to be a manager, and much of the educational literature ignored this area. Organisational literature such as Bruce Patton’s Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most were therefore essential in helping me tackle complex interactions with colleagues, senior leaders, parents, and pupils. So, push yourself beyond the standard texts and theories to become a more well-rounded practitioner.

Tip 5: Collaborate

When I was putting together our application to achieve Research Mark+ from the Chartered College, one of the most heartening aspects was writing about the collaboration that occurs across the school and beyond. But this culture did not appear overnight. As teachers with heavy workloads, we often want to pull the shutters down and remain focused on our interactions with pupils, rather than the colleagues around us. However, creating time and space to share will help foster these support systems and learning networks. This could be by encouraging reciprocal learning walks, engaging in a programme of internal CPD, or attending smaller working parties to tackle problems. My first working party as an ECT focused on marking and feedback, where I learned a lot from my more experienced colleagues and felt empowered by being part of school-wide interventions based on the research. In recent years, I have started to collaborate more with local schools as part of a broader teaching and learning network. It has been useful to see how interventions play out in different contexts, and we have all benefited from sharing ideas, policies, and strategies. Connecting with others within and beyond your school brings so much value, and there is no limit to the networks you can create.

Conclusion

So, after completing your ECT years, it is normal to think: what next? You may find yourself settling into the rhythm of teaching life and be thankful that the paperwork and self-reflections are now behind you. However, you will feel more invigorated and confident in your career if you maintain a positive trajectory with your professional development. Supercharging your learning through education research and exploring the world beyond your classroom will help you become a more holistic practitioner, ready to face whatever challenges the rest of your career throws at you.

Bibliography

Agarwal, P. et al., Powerful Teaching: Unleash the Science of Learning (2019)

Casey, B. J. and R. J. Jones, ‘Neurobiology of the Adolescent Brain and Behavior’, Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49 (2010)

Daly, C. and A. Pollard, Reflective Teaching in Secondary Schools (London, 2023)

Jones, K. Retrieval Practice: Research & Resources for Every Classroom (2019)

Patton, B. Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most (2011)

Rosenshine, B. ‘Principles of Instruction: Research-Based Strategies That All Teachers Should Know’ in American Educator, 36 (2012)

Sinek, S. Start With Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action (2011)

Link: https://teacherhead.com/2019/02/12/curriculum-notes-2-big-picture-first-then-zoom-in/

Link 2: https://www.educationalneuroscience.org.uk/resources/the-adolescent-brain/